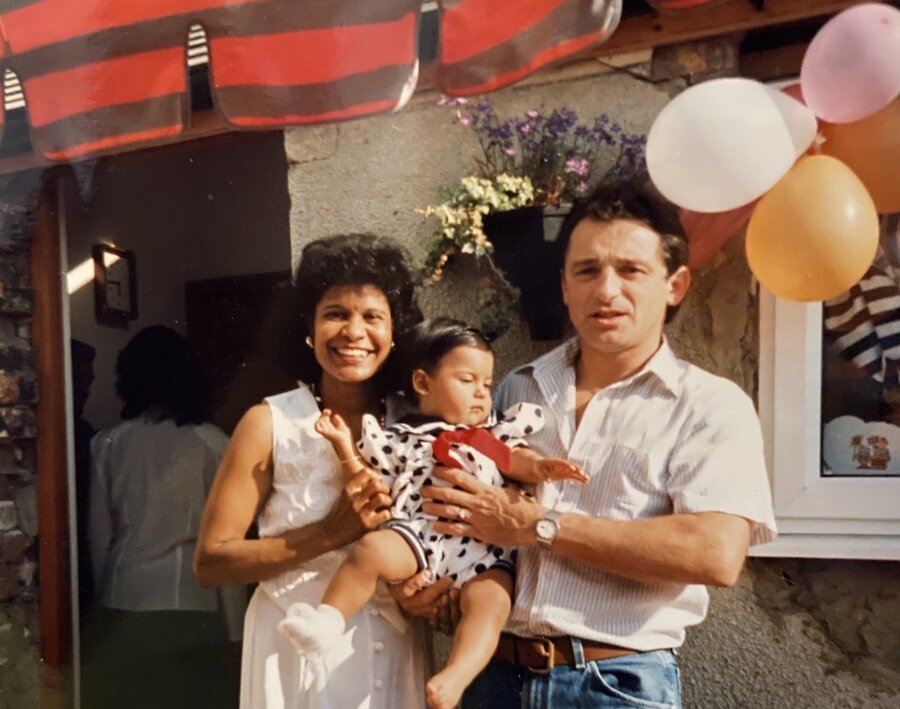

Nicole Margarita Henworth

[1995. This picture was taken in the back garden on my 1st birthday. My mum, me and my dad. There’s very few photos of the three of us together, and it’s been weird to revisit. This photo makes me realise how much change I’ve been through, and that regardless of how life takes it’s path, these two represent my roots.]

1994 | Deal, UK | English, Sicilian & Trinidadian (Indo and Afro-Caribbean)

Anyone who knows the little seaside town of Deal in Kent, will understand I grew up in an all-white area. I was always the ‘brown’ kid. When my annual primary school photo was delivered, I could spot myself within seconds alongside the token eye patch kid. Kids would always ask if my white dad was really my dad, and being so young I never understood it all. All I knew was that this olive skinned, blue-eyed man was my dad and this beautiful dark-skinned woman with big hair was my mum and I subsequently was an amalgamation of the two. I remember at parents’ evening, the penny would drop whilst we queued up to speak to the teachers; we’d look like some sort of mathematical equation – English Italian dad + Trini mum = Nicole. After events like this where we were all together and the obvious was stated, the questions and curiosity towards my racial ambiguity would subside.

My mum came over to the UK in 1973, and like many West Indian women, wanted to pursue a career in nursing. In 1984 she was given the opportunity to join Buckland Hospital in Dover. My dad was the patient and my mother the nurse. After a few months he plucked up the courage to ask my mum out on a date, but could only remember her surname. Legend has it, he went through the yellow pages to find her number and the rest is history. But don’t let his old school energy fool you, my parent’s relationship was extremely tumultuous, but that’s a story for another time. When I was around six, my mum’s sister and her husband in America stepped in and took me under their wing. Every summer holiday was spent with them and in time I celebrated Christmases with them too. When I was 12, they had their son Jude, he was introduced to me as my brother and we’ve been inseparable ever since. From this casual transatlantic adoption between the UK and US, I was immersed in the Trinidadian culture from small. I’ll never forget annual reunions where Christian, Hindu, Muslim and Rastafarian family members would all be under one roof. Aunties and uncles would cook a plethora of traditional food, with its origins rooted from all over the world. I grew up on the musical fusion of Calypso, Soca, Reggae, Chutney, Parang, Lovers Rock and old school Bollywood and just knew that this was normal, this was family, this was love.

My mother has always been a hard worker and such a stickler for a clean and presentable house. She’d work long night shifts in the hospital, cook, clean, get around five hours sleep, tend to me and then do it all over again. I never understood why she was so strict. I had beatings with almost everything, the slipper, the flip flop, the wooden spoon. Don’t let my mother’s meek 5ft stature fool you, that West Indian hand gave licks in syllables, and the smallest vexation would see her quiet English tone turn into a bellowing Trini patois. When mum became sick in 2008, she soon after retired due to her ill health. It was during this time we became closer, I could finally ask her questions about her culture, her ancestry and her story. I’d hear her playing the music she grew up on whether that be Mohammed Rafi or The Mighty Sparrow. I loved it when she cooked my favourite stew chicken, the browning of the sugar and oil echoed an aromatic nostalgia. I naively thought my mother’s retirement would be the perfect opportunity to have a normal family life, a chance to have a balanced cultural upbringing with both parents, but unfortunately the relationship with my father became even more strained. I began to notice that my mother would tone down her culture around him, she’d turn the music off, or cook English food to please his palate (he didn’t have a relationship with his mother, so British culture was all he knew). My parents eventually divorced when I was 18 and my father has been estranged ever since. As humans, it’s natural to follow a path of love and that’s exactly what I did. However, as a mixed-race person, this bittersweet adjustment meant I was subconsciously losing the gateway to my English/Italian culture and embracing my Caribbean side.

Growing up I understood that being mixed race you had to be half black and half white. I felt like I couldn’t fit in with the white kids, but then I also wasn’t fitting into this stereotyped mixed-race criteria. I didn’t have tight curly hair, I had long wavy hair. I didn’t think I had any European features, but thick eyebrows and dark brown eyes. If I told people I was half Caribbean, I’d usually receive the response, but your mum looks so Indian, how can she be Caribbean? I’d then have to overstep the ignorance and educate them on West Indian history and the migration of Indian indentured labourers in the 1800s, and explain my mum’s mixed heritage. I’d have to clarify that not all West Indians are purely Afro-Caribbean and that there are countries in the Caribbean other than Jamaica. This very experience has made me realise that if people struggle to understand the mixed racial history of the Caribbean, then how on earth would they have the open mind to comprehend my personal mixed heritage?

I wish people understood that your racial mixture doesn’t determine your cultural knowledge. Just because we are mixed race, that does not mean we are equally educated on our lineage. If two parents of the same ethnic background separate, culture is never really an absent factor to their offspring. But with a mixed-race person, it could deny them the natural guidance to understand their genetic makeup. If I tell you my grandmother was Italian, don’t assume I’m fluent in the language. If I tell you I’m half Caribbean, don’t assume Bob Marley was king of our speakers. Being mixed race is far more complex, we adopt little fragments and if you were to line up mixed race people from the same ethnic background we’d all be totally different. I’ve also noticed at times people will look down on me and assume that they must know far more about a culture because they’re monoracial. I’m never White enough, Asian enough or Black enough. I loved it when once I shut a British Jamaican girl down - she told me I could never be as Caribbean as her, yet she’d never been to her motherland and was clearly surprised that I visited Trinidad every other year and had strong ties to the island and took interest in my ancestors.

At 21 I moved to London to pursue my Masters Degree and it was the best decision I could have made. It was the move I needed to figure out who I was and what I stood for. I moved to South London where a Church, a Gurdwara and a Mosque were all on the same street. I finally had access to talks, exhibitions and classes that could educate me further. I could ultimately meet and surround myself with people like me. In this metropolis, filled with beautiful ethnic diasporas, I finally fitted in.

If there was anything I could let my younger self know it’s that all this confusion will come to rest and you’ll find happiness with who you are. You’ll reach your mid-twenties and realise that you’ve come to terms with not fitting into a criteria. By being White, Asian and Black you can bring a unique perspective to life, a level of empathy to the social make-up of the world. You’ll enjoy teaching others about your cultures and educate them on growing their minds. You will learn to be unapologetically you, a far cry from the little girl waiting for people to complete the mathematical equation.

[2019. This was taken in front The Alamo, Texas. Me, Uncle Vaughn (my uncle dad), Jude (my little brother), Aunty Sarah (mamacita) and My Mum (who I lovingly call Shoya - her Trini childhood nickname). This photo makes me burst with happiness. I feel blessed as not many people are lucky like me to have family step in as parents. I have so many amazing memories with them and it fills my heart to know that we’re making so many more as my brother and I grow older.]